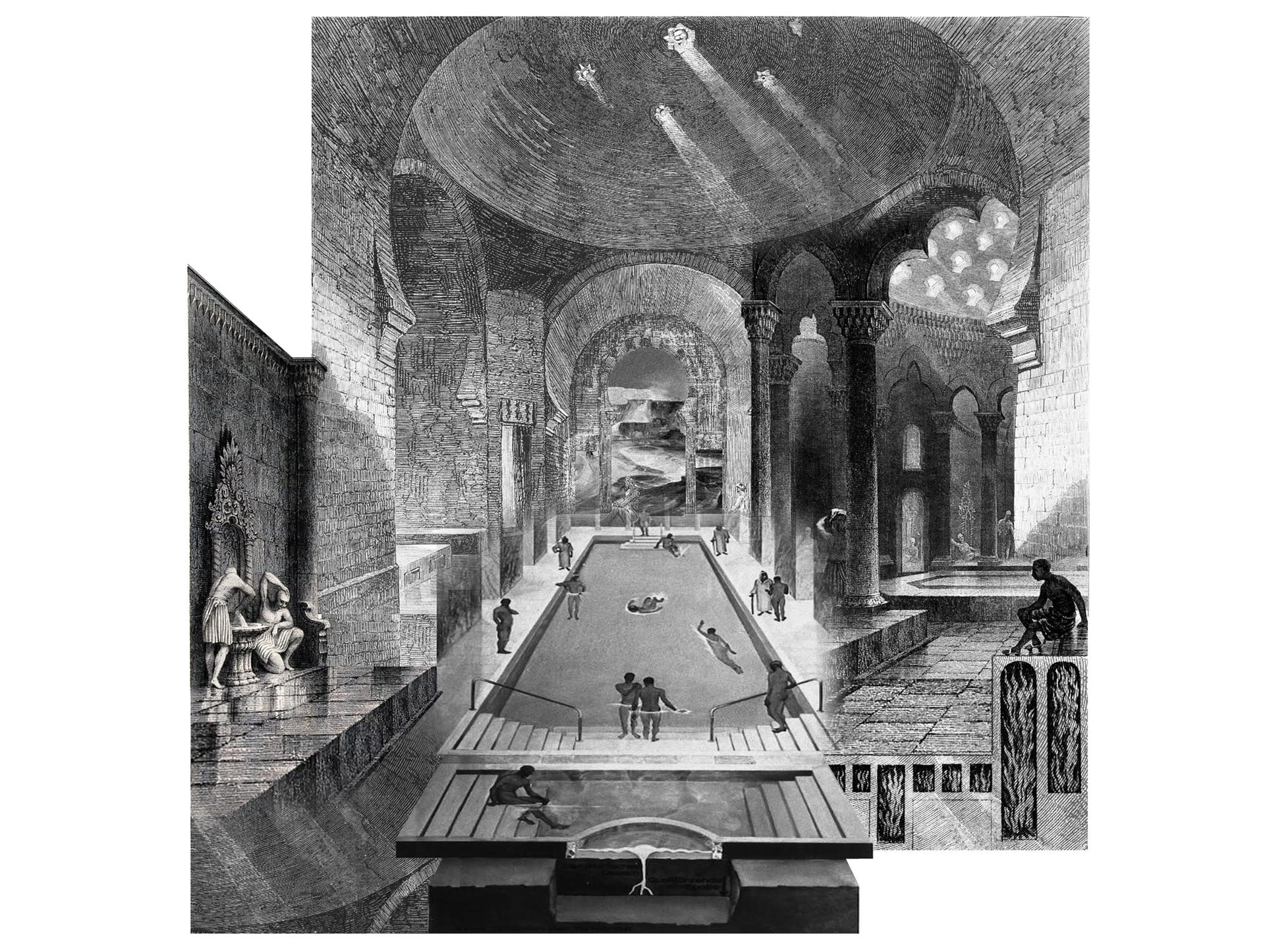

This project brings together my experience as an NHS patient, conversations with NHS medical and strategic staff, and mentorship with practicing healthcare architects. I am also learning from the rich architectural history of health that runs deep through every culture, with the healing spaces of ancient civilisations mediating the temple and the doctor’s house, and ancestral practices persevering in communities around the world. Through harmonising this research, I arrived at the following design philosophy:

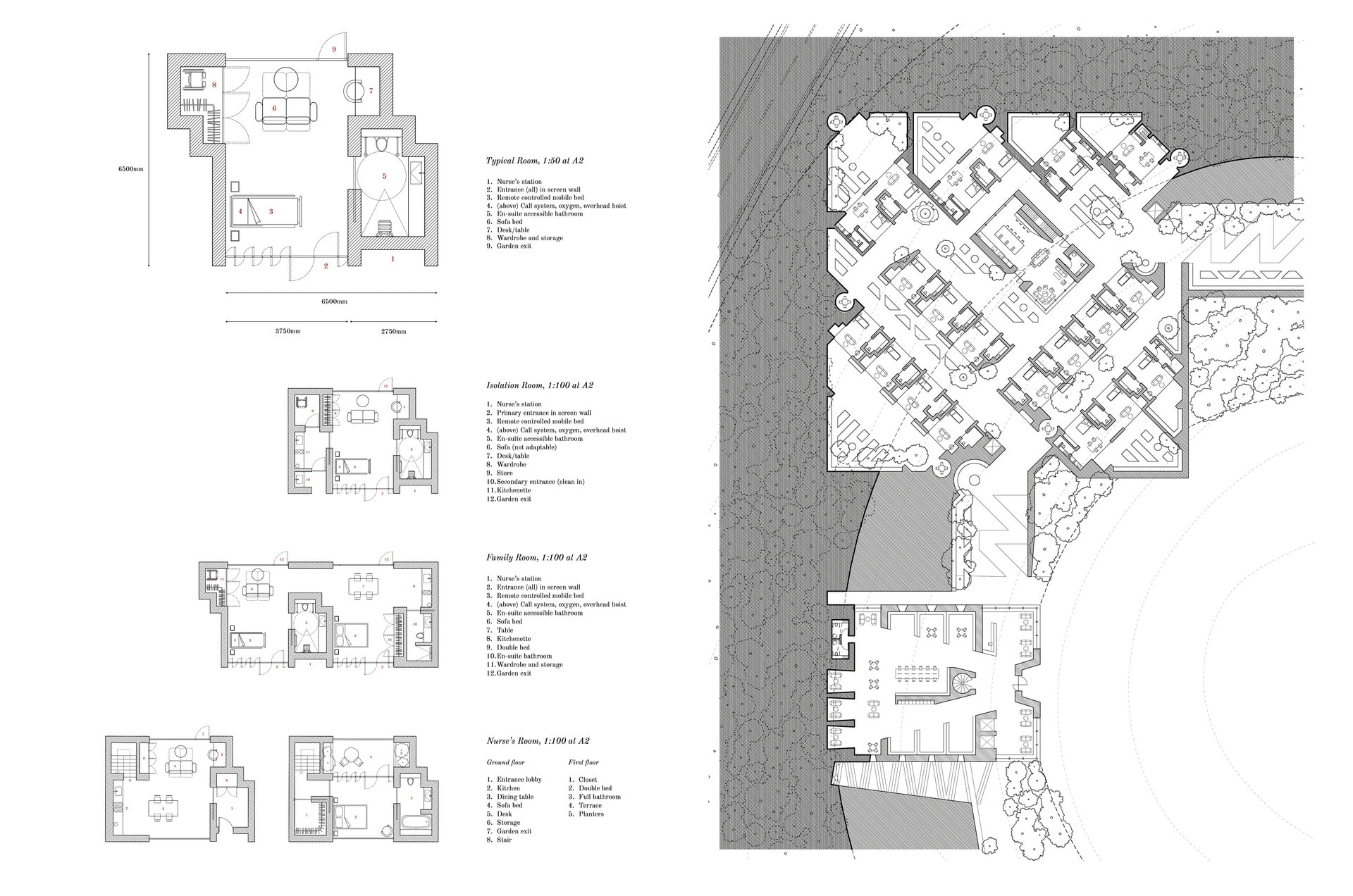

Firstly, I believe in the agency of the patient in overcoming illness. My proposal advocates means of healing beyond conventional medicine; in the words of Maggie Jencks, to help patients find ways of helping themselves. I use hydrology and the tidal cycles on site to craft multi-sensory experiences, and approach the site as a garden and a cornucopia of food and medicine, asking how processes and rituals of healing the body can be synthesised with those of healing land.

Secondly, I embody the architect’s duty of care to the climate, user and construction worker by decarbonising and de-toxifying the construction of healthcare buildings, employing and reusing land and materials for their longevity and negative embodied carbon, and making the most of opportunities for renewable energy.

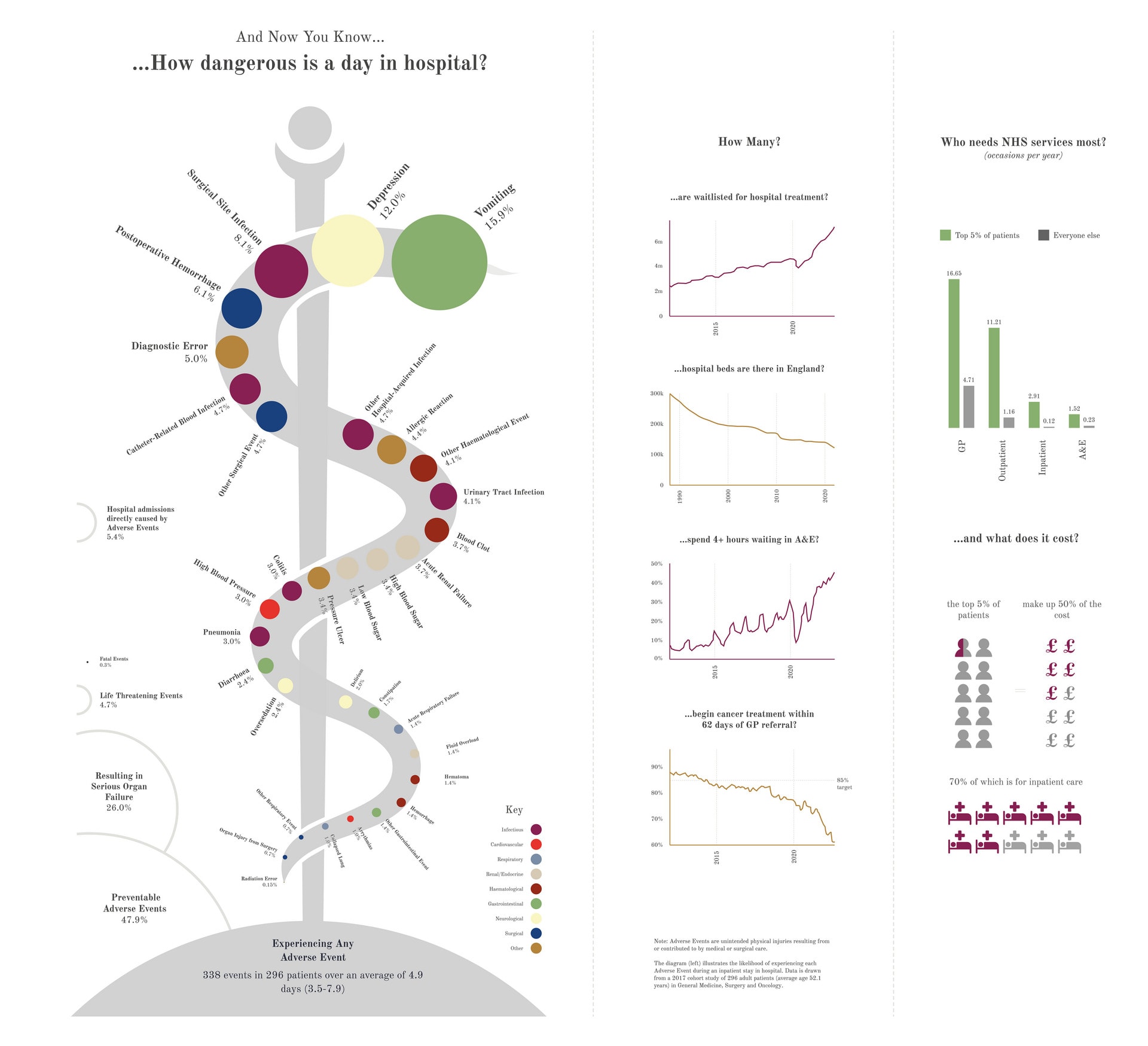

Finally, the NHS now exists in an ever-deepening state of crisis, but it also stands at the pinnacle of evolution beyond the mega-hospital. 5% of users need the NHS more than the other 95% combined, and a large part of our struggles for GP appointments, hospital beds and emergency services are due to a lack of care in the community for those who need it most.

Therefore, this project proposes assisted living housing alongside physical and psychological treatment spaces for patients with longer-term health conditions as well as day visitors. It eases pressure from the broader NHS, unites the security of the hospital with the autonomy of home, and affords the long-term patient freedom from fear, as help is always just a moment away.

As I began my search for a site, I questioned what we might learn from all these histories and rituals of health, and where we might find our contemporary parallel?