‘Nothing that is expressed is obscene. What is obscene is what is hidden.’ - Oshima Nagisa

The first time I ever saw an erotic Japanese art house film was the night I moved to Tokyo. Having screwed up my arrival date with my landlord - ergo, having no access to my humble new ‘danchi’ abode - I ended up crashing at a Polynesian themed Love Hotel in Shinjuku for the night; one of those neon-sign-baring sex dens with the gaudy wallpaper, futuristic robo-toilets and battery-powered beds that cater to Japan’s sexually frustrated youth. Or at least that is the type of clientele these joints aimed to accommodate during their inception in the 70s - a time when youngsters still living with their folks were unable to consummate their sexual desires behind the wafer-thin walls of their parents’ stifling post-war block apartments. These short-stay suites - whose mirror-plastered ceilings, water mattresses and gussied up decor became synonymous with the sleazy bubble era nightlife of the 80s - provided Japan’s youth with some much-needed privacy. As for me, they simply provided a cheap, no-res-needed crash pad for a night or two.

I got to the reception at a little past one and was immediately greeted by a delicate pair of alabaster hands that had emerged from a slit in the wall. After ever so discreetly handing me my keycard, both of our anonymities still intact, I made my way up to my Kabukicho ‘no-tell motel room’ - rotating circle bed, artificial silk sheets and all. Having used up all my Ambien and not disciplined enough to try and fight off the jetlag without, I reclined and felt around for a remote in hopes of finding something decent on TV; a subtitled Satoshi Kon picture or a Yakuza flick or something like that. I eventually located a Toshiba clicker alongside some litre containers of lubricant not so subtly disguised as bottles of shampoo (for modesty, of course) and once I got my bed to stop spinning, I began flicking through the channels for some late-night siesta-inducing entertainment.

The genitals of an old homeless guy fill the screen as they are hit by small fistfuls of snow. Naughty children have found the man sprawled out, laying comatose outside a Tokyo hotel - surely anaesthetized from a few too many Asahi’s the night before. They seize the opportunity to lift open his scraggy kimono with the stick end of a Japanese flag and get up to some devilry.

The film I had landed on was Oshima Nagisa’s 1976 release, In the Realm of the Senses - a film based on the true story of Sada Abe, a geisha/prostitute who killed her lover via erotic asphyxiation before hacking off his genitals and carrying them around Tokyo in a kimono. While not quite a porno, (despite its wealth of unsimulated sex acts including a blow job that makes Brown Bunny look like it's rated PG and a geisha gang bang that left me never looking at wooden bird sculptures quite the same way) the film wasn’t really a regular Oshima New Wave picture either - something i’ll get into later. It was more of an arthouse meets grindhouse type of film - a blurring of art and pornography, kind of like the films of Gaspar Noé or Lars Von Trier - but without the kind of titillation you’d expect from the sexually injected television screens of Japan’s love hotels.

It was in the late 60s that the first tape players hit Japanese markets and by the time love hotels had started becoming hot commodities in the early 70s, personal televisions became something of a love hotel staple. Naturally, with the kinds of activities that such establishments aim to accommodate it made sense that the channels would showcase something a little kinkier than Mobile Suit Gundam-style anime and indeed, production companies like Shintoho and Ôkura Eiga seem to have supplied love hotels with videos of a steamier kind.

Oshima’s biopic nudie shouldn’t have seemed that unusual in a place like this and yet it most certainly was. Sure, there was lots of nudity and a ton of sex, but it seemed to me that this was a porno with no real intention of arousing its audience at all. In fact, for any couple seeking to enhance their sexual escapades with a bit of erotic stimulus playing in the background, Oshima’s lurid film would have been one hell of a turn off.

Oshima and Unerotic Pornos

Oshima had been somewhat of a shot in the arm when it came to my enamorment with Japan and its cinema. I had been mildly obsessed, if there is such a thing, with the New Wave cinema of Hong Kong and in particular its second wave, of which Wong Kar Wai acted as head honcho in terms of the movement’s defining auteurs. Inevitably this got me sniffing around some of Asia’s other New Wave movements and once I dove into the rabbit hole of Japanese cinema, I found I couldn’t get back out. Interestingly, the term honcho is derived from the Japanese ‘hanchō’ or ‘group leader’ - it’s not Mexican in origin as many people have come to believe. The term gained popularity in the States in the early 60s but was initially absorbed into the American lingo in the 40s by US servicemen stationed in Japan who brought the term back with them when the occupation ended, and troops returned home. These occupation and early post-occupation years represent an era that marked and bred a generation of avant-garde filmmakers in Japan - those of the Nūberu bāgu, the Japanese New Wave - and Oshima Nagisa, as it turned out, filled the position of head honcho.

It is surprising then that this film of Oshima’s that I watched that first night in Tokyo is probably his best-known work despite the fact that it wasn’t anything like the New Wave films that made him a household name on the international film festival circuit. In fact, his tour de force wasn’t actually released until 1976 so it didn’t really belong to the New Wave genre anyway with the movement having already faded away by the early 70s. And it can’t even really be considered Japanese, as while it was shot in Kyoto, L'empire Des Sens (its original title) was technically a French production - one that wouldn’t have come into fruition were it not for Oshima’s Cannes-born friendship with Anatole Dauman (the guy who produced films like Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima Mon Amour, Christ Marker’s La Jetée and Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin-Feminin).

Like I said, the film really didn’t give off even remotely the same feel as Oshima’s usual New Wave stuff, or anything else he had made up until then for that matter. It could be that he was influenced by his New Wave counterpart, Imamura Shohei, who aroused controversy with films like The Insect Woman (1963) for his intense interest in sexual themes - in the relationship between the lower part of the human body and the lower depths of Japanese society. Or perhaps it was the fact that Pier Paolo Pasolini’s equally fabled Salò came out just the previous year - a film adapted from the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom. While it would be far too simplistic to whittle the film down to an ‘orgy of violence and degradation,’ the nausea-inducing feces force-feeding scene combined with the mass rapes, pedophilia and executions makes Pasolini’s magnum opus something like ‘the mother of repulsive and controversial films’ - at least in the cinema of the West. And while Oshima’s picture isn’t nearly as depraved, when it comes to pushing the boundaries with politics and sex, Salò could have certainly been an inspiration. It is also notable that Oshima wasn’t the first to adapt the story of the sadomasochistic castrating geisha into film, as A Woman Called Sada Abe came out just a year earlier - a film directed by Noboru Tanaka, known for his work in the theatrical pornographic film world of the ‘Roman Porno’. If you look up the film’s credits, however, another even more direct influence will hove into view with Koji Wakamatsu listed as the film’s co-screenwriter and assistant director - a guy known in Japanese cinema as the Godfather of the independently produced, low-budget, softcore porno movies known as pink films.

The pink film

The pink film (or pinku eiga) has lurked in the murky underbelly of Japanese cinema since the early 60s. It's the type of film you may have found flicking through the channels of a love hotel television set before the hardcore porn tapes of the adult video industry took over. Yet it wasn’t on the small screens of these hedonistic short stays that most pink films were originally enjoyed but rather the remodelled ‘adult only’ cinemas whose softcore screenings would help keep Japan’s movie-going industry afloat. Satoru Kobayashi’s 1962 erotic crime drama, Flesh Market, is generally accepted as the first ever pink film and it was born out of an era marked by the rise of television, the resultant crash of box office returns, the bankruptcy of the major studios and a nation of emptying theatre seats. With theatres unable to fill their double or triple bills, a new kind of film was needed to lure audience members back to the cinema in ways that the majors had not. This is where the kinky softcore indies of the pink film ‘genre’ came into play and by the 1970s this sub-industry was already booming with audiences flocking to their local Pink theatres to catch the triple-bill screenings of a genre that now made up almost half of all the films produced in Japan.

I put genre in quotation marks here because despite a couple of unwritten rules that pretty much congealed into place by the early 70s, (shooting 1 film of around 1 hour in around 1 week on 35mm film, guerilla-style and with a rather pathetic budget) these ‘three-million-yen films’ or ‘eroductions,’ as they have also been called, don’t actually fit into any particular genre in the traditional sense. According to Jasper Sharp’s 2008 work, Behind the Pink Curtain - a Pink bible of sorts that summons its readers into the hinterlands of Japan’s underground erotic cinema scene - what really defines the pink film genre is not its content or even its eroticism but rather its means of distribution and production.When it came to subject matter, as long as pink filmmakers met their quota on sex scenes and nudity, they could pretty much make anything from a surrealist cyberpunk slasher to a cowboy space operetta.

For pink filmmakers, most of whom were university graduates, (a prerequisite for those wanting to get hired in the Japanese film industry) working on a skin flick provided just as good of a starting point as any. And while titillation may have been the main target, things like mise-en-scene, camera angles, script and soundtrack were given much more attention in the production of a pink film than that of your average dirty movie. The subgenre provided young filmmakers with a directorial gateway drug of sorts and a space of seemingly infinite artistic freedom. But while the pink film industry has produced some genuine cinematic knockouts - turning out some of the most mind-bending, wildly experimental and hallucinatory pictures of the Japanese indie scene - the reality is that the bulk of these types of pictures delivered little more than the cheap titillation and paper-thin narratives that they promised.

It’s true, most pink films were trash - smutty stag films that were dispassionately watched and then taped over to be consumed again. Pink Theatre patrons were no cinephiles either, but most likely horny salarymen on their lunch breaks chasing after an airconditioned room. You could find them lounging around the theatre like a bunch of sweltering legumes, their chain-smoking fumes flirting with the dust particles by the projector as the no smoking signs remained diligently ignored. Other Pink Theatre frequenters were the seedy individuals of Japan’s bubble era 80s who used the sheltering darkness of the cinema’s dimmed lights to solicit blowjobs and double masturbations. But pink films and their theatres weren’t always this tragic, if you consider the exception and not the rule. And Wakamatsu Koji was certainly an exception.

Wakamatsu films weren’t at all like the other cinematic junk food that was out there. For one, several of the films he produced in the late 60s and early 70s were screened at European film festivals - something unheard of in the eroduction orbit at the time. While most pink films were made to be scarfed down and forgotten, Wakamatsu’s pictures - often drenched with maddeningly elusive political allegory - crossed over into the realm of subversive art. Art still venerated by Japanese cult film enthusiasts to this day. His socially conscious pornos, as I like to call them, were not consumed in the usual dispassioned salaryman fashion. Rather, ‘people would watch them quietly and intensely, even reverently’when Wakamatsu was in his prime. The political porno brainchildren that branded Wakamatsu a radical filmmaker blurred the lines between art and pornography, serving as visual testimonies of an age of sexual expression, student rebellion, burgeoning left-wing radicalism and sweeping post-1960 disillusionment. For Wakamatsu, who died in 2012 after being hit by a Shinjuku taxi, these films are the legacy of a director that was forever raging against the machine.

As an ex-con and ex-Yakuza member whose connections got him into the biz, Wakamatsu’s entry into the pink film arena was almost as unconventional as the movies that made him famous. Back in his directorial salad days however, Wakamatsu drank the Pink industry Kool-Aid just like the rest of his eroduction compatriots did. The workaholic director produced something like 100 films and most of his output - titles like The Love Robots, Dark Story of a Japanese Rapist and Orgy - simply catered to the flavour of the month. It was through these run-of-the-mill features however, that Wakamatsu and his collaborators could fund his more experimental works - films like his 1966 psychosexual bondage masterpiece, The embryo Hunts in Secret, for instance - and exploit the distribution system that the eroduction industry hereby provided.

The Dawn of Political Pornos

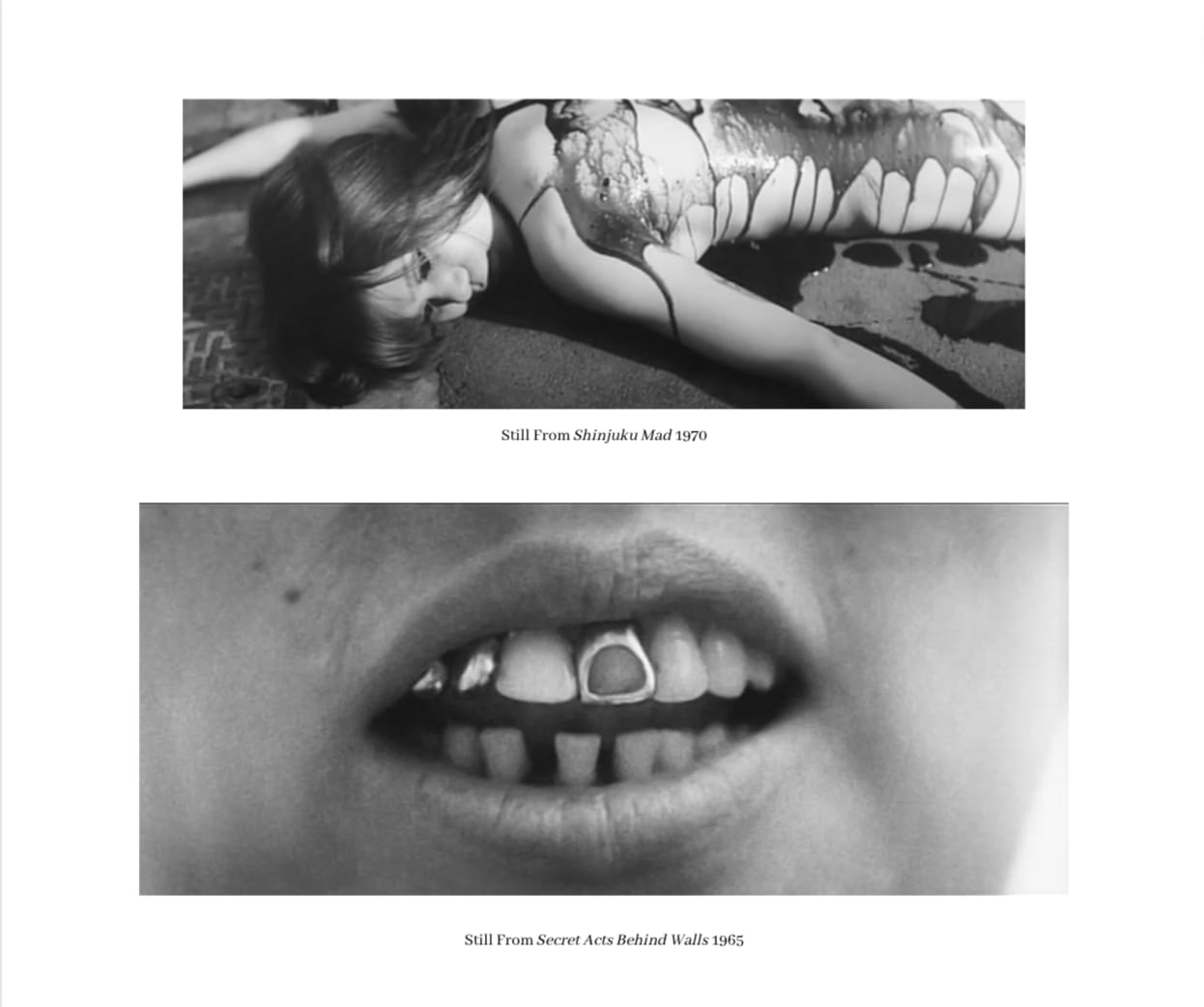

Wakamatsu’s first real stand-out picture was released a year following the 1964 Tokyo Olympics when, by the sweat of Japan’s brow, the games had restored the country’s global status ‘from post-war pariah to high-tech go-getter,’ leaving the land of the rising sun to bask in a state of modest pride (á la Japonaise). Broadcast for the first time in glorious technicolor, the 64’ Games provided Nippon with a tentative sense of security. Their global popularity was at an all-time high as somewhat of a selective amnesia took over, shrouding the atrocities of war under a new kind of patriotism - one that involved some good-old fatality-free combat between nations. It was but a year later that an overseas screening of a different sort would once more garner international attention; one that threatened to corrode Japan’s recently achieved lily-white image by drenching it in pink-tinged controversy. We are of course talking about Wakamatsu’s iconic tenement block flick - his 1965 “succés de scandale”, as David Desser calls it - ‘Secret Acts Behind Walls’.

Secret Acts Behind Walls was the first of Wakamatsu’s eighteen prior works and the first picture from within the pink film ether to catch the glimpse of overseas eyes after a succession of strange fortuities led it all the way to the 1965 Berlin Film Festival. The picture wouldn’t have even made it to domestic screens if Wakamatsu hadn’t presented a different script to its financiers, potentially risking any future funding if things backfired and they didn’t rake in a profit. The commissioning company, Kanto Movie, approved the project and it wasn’t until the whole thing was wrapped and edited that they realised Wakamatsu had taken them all for a ride. Needless to say, upon seeing the final product, with its Little Boy aftermath overlays, incestuous rape scenes and Vietnam War references (all of which I will delve into in a later chapter), the people at Kanto were foaming at the mouth. As it turns out however, the film would have its investors lining their pockets - in large part because of some German guy from Hansa-Film (As Wakamatsu referred to him) who, after catching the film during a visit to Tokyo, ended up submitting it to the Berlin Film Festival. It wasn’t the prestige of the festival that led to the film’s domestic success, however. Quite the opposite in fact.

Any of the film’s artistic merit was hastily dimmed by scandal as domestic newshounds ventilated the dirty linens of Japan’s film industry for the second time that year. The first director to land in the gutter press was Takechi Tetsuji whose 1964 and 1965 cult-classics, Daydream and Black Snow led to a high-profile obscenity trial. It wasn’t the full-frontal nudity or rape scenes that got the censors on Takechi’s track, however - far more salacious and pornographic films had gone unscathed in the past. Rather, it was his treatment of the nude body as a political allegory for the US military presence on Japanese soil that got him into trouble….