Much like my favorite hero Odysseus, I have a love-hate relationship with words. Unfortunately, I was born with severe dyslexia, dyspraxia, and visual stress. Fortunately, as much as my dyslexia has attempted to sabotage everything I write, I have still, ironically, managed to graduate with an English and Classical studies degree, and a Masters in History of Design.

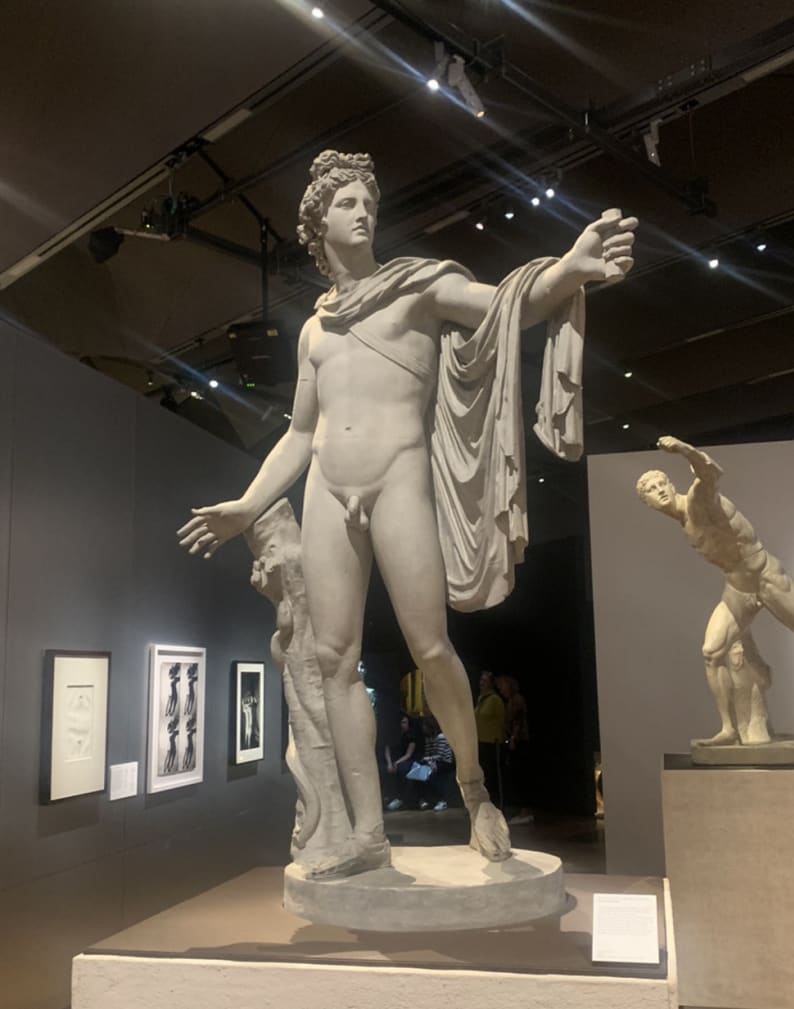

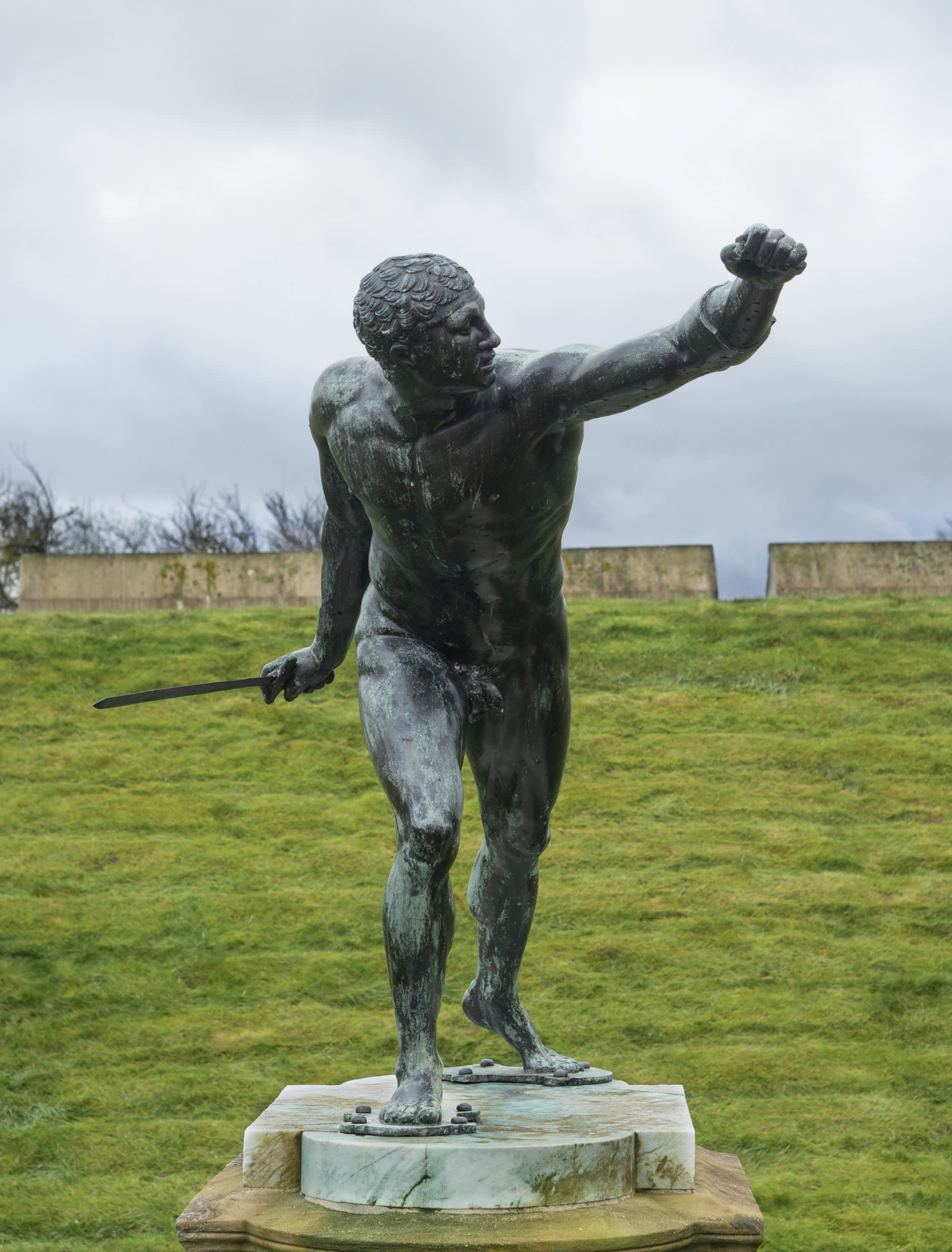

As a design historian, I have studied the way in which collecting habits from the Italian Renaissance to the modern day have shaped lasting concepts of design and aesthetics. In particular neoclassicism, in sculpture and ceramics has been the key focus of my research at this programme co-run by the V&A Museum and the RCA.

I believe in making objects and art that embody the contemporaneous thoughts and feelings of our societies accessible to all, through research, curation, and communication.

V&A Sylvia Lennie Award recipient