I am a researcher, writer, and editor interested in the social and cultural histories of fashion.

My previous research looked at how late-nineteenth-century academic women in the UK dressed. I was interested in the notion that while the modern woman in London was characterised by her fashionable short hair, trousers, and her Crème de Menthe frappe drinking at Cafe Royal, women students were depicted as dowdy blue stockings having rejected the frivolities of fashion in lieu of more 'serious' interests. I looked particularly at women studying at Oxford and argued that they challenged the ‘cultural intelligibility of women’s fashionably-dressed bodies as docile and ornamental’, not by rejecting fashion but by reformulating their relationship to it.

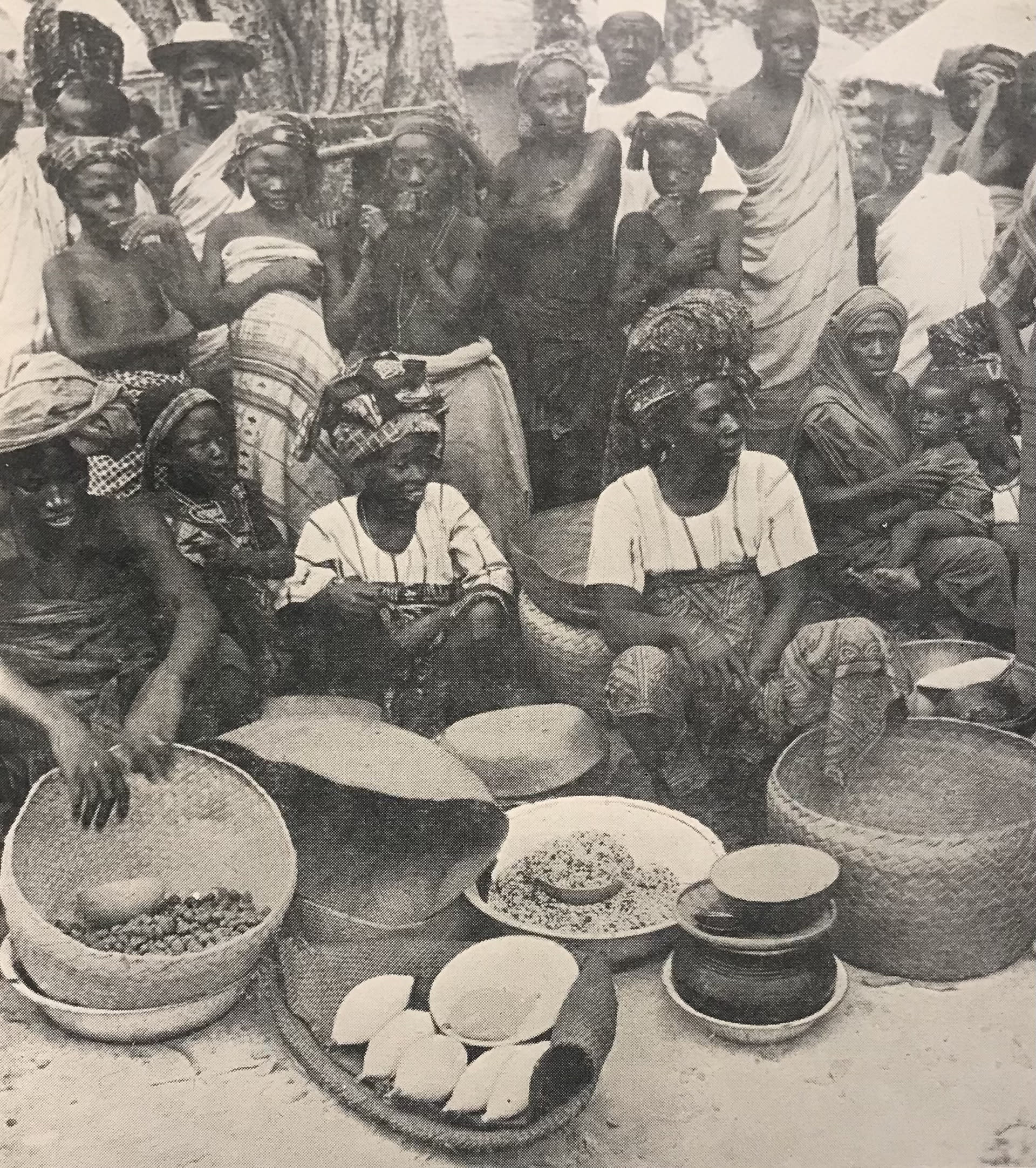

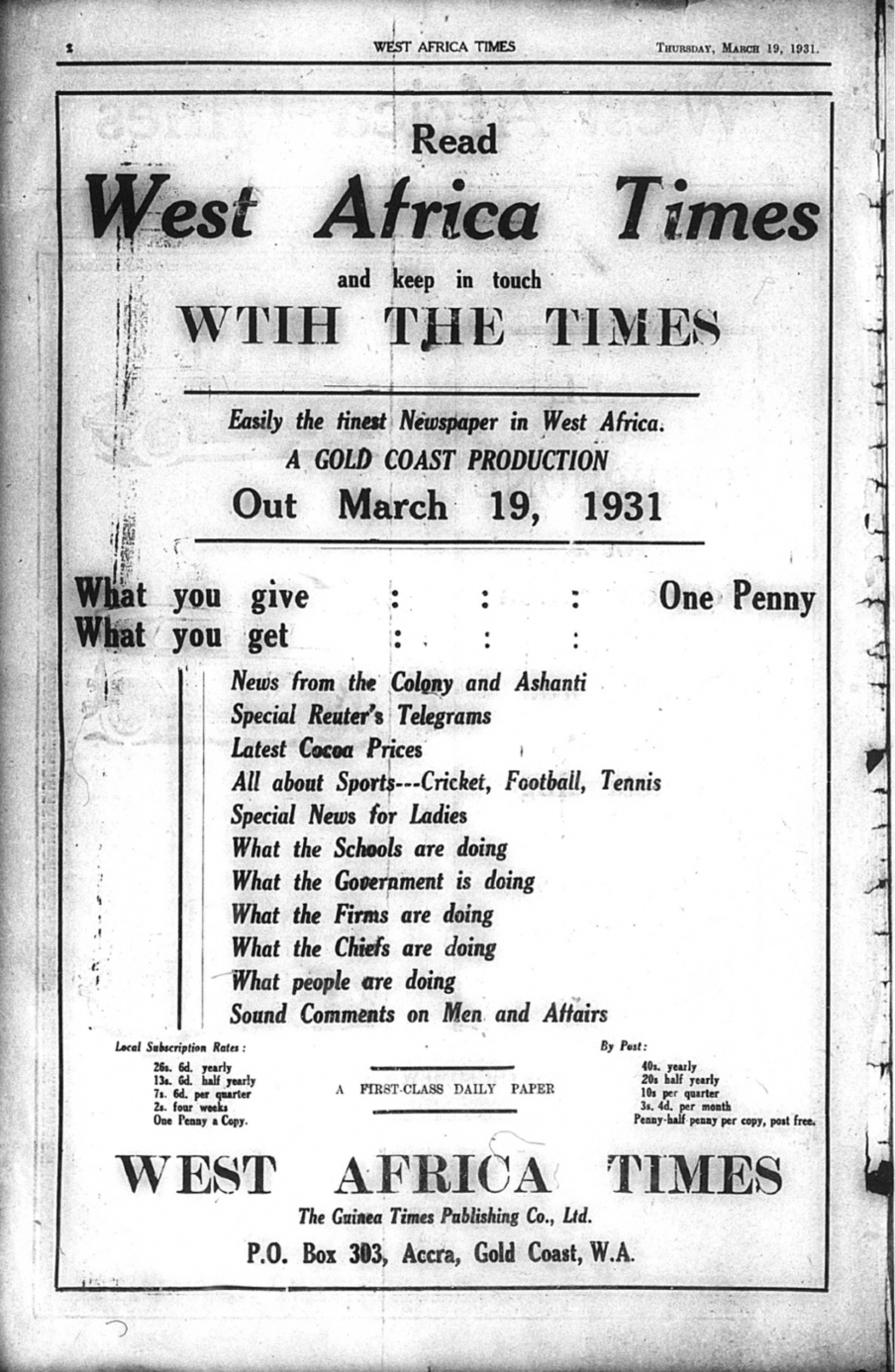

My research on the RCA/V&A programme continued looking at the themes of fashion, gender, and education, however, my area of focus shifted. After seeing the Africa Fashion exhibition, I started looking at West African, particularly Ghanaian fashion cultures. Missionary education and the import of cotton cloth were central to colonialism in West Africa. My Object essay focussed on the production (in Manchester) and consumption (in West Africa) of an alphabet wax print that 'allude[d] to the value of education' Following this research, my MA dissertation explored discussions of fashion in the interwar urban press in Accra, Ghana.